This article is co-authored with SpencerDub (NISEI Media Pipeline Coordinator).

Previously we have learnt how to acquire resources (efficiency) and how to have an objective (strategy). If you are coming to this article first, you should seek out and read the previous ones to get the full value of this text.

Tactics is about converting those resources into what you need to win the game. Making moves. We will adopt a purely board-state-focused mindset here, and not deal with psychology.

First, as usual, time for some definitions.

Tempus fugit. Mind your clicks.

Tempo, what is it?

Tempo can be a hard concept to understand if hearing it in casual conversation. It is a bit hard to nail down as well, but very useful and very integral to thinking about tactics in card games. Think of everything you have in front of you when playing a match as ‘potential for actions’. Credits, programs, ICE, cards in hand.

These resources are what will allow you to win the game. They are the tools that allow you to execute your strategy faster then the opponent executes theirs. They are usually referred to as your board-state. If you would start the game with more credits (say, 15) you would have a massive head-start on your opponent towards executing your strategy before them.

Tempo likely comes from the Italian word for ‘time’. In a card-game simply refers to the total accumulation of your useful resources. Specifically resources that helps progress your strategy.

Tempo-advantage means who is accumulating or progressing faster in these resources, or board-state.

Note that the resources need to be useful for you. If you have drawn a small ICE late in the game, or drawn a duplicate of your breaker these do not give you tempo. In the opposite they likely cost you tempo since you expended a useful resource (click) to draw a useless card.

Credit Advantage

A very good example in Netrunner is credits. We all know that being at zero credits is a massive difference from being at 5, or at 10. Losing 5 credits if you are at 10 is less harmful than losing them when you are at 5. If you have 30 credits, an additional credit does not really matter.

Thus the tempo of credits depend on how many you have, and also how many you expect to spend in the near future. If you don’t need them to win, they offer you no tempo.

Card Advantage

This is less important in Netrunner than in, say, Magic. In Netrunner you can control the pace at which you draw, but cards in hand still allow you to do powerful things.

More importantly, as defined in the efficiency article is deck-access. The % of your deck that you have seen. If you have seen 50% of your deck the likelihood that you have your critical counter card (Clot, say) is much higher than if you’ve seen 25%.

Board Advantage

This is harder to define, as cards are so varied, but you can feel it while playing. Both sides have a wanted-state of cards that they need in front of them to be at full power, and until you get there the game is a continuous struggle of choosing when to build board-state and when to progress towards the strategy.

For a Runner this is a full rig with all permanent economy out, and for a Corp it is whatever optimal configuration of ICE and remotes they need to execute their strategy.

Tempo Advantage

Think about all of the above together as a single resource: tempo. Whoever has the tempo advantage has another very powerful effect on the opponent, in addition to just having it. If the game progresses from here with no change they will reach the finish line first!

This has a forcing effect on the opponent, they ‘must do something’ to flip the tables, and regain the advantage. This forces the opponent to take more difficult decisions, while you can concentrate on playing efficiently.

Whoever has the tempo-advantage has ‘the ball’.

Are you ahead, or behind?

Lean in or Lean out ?

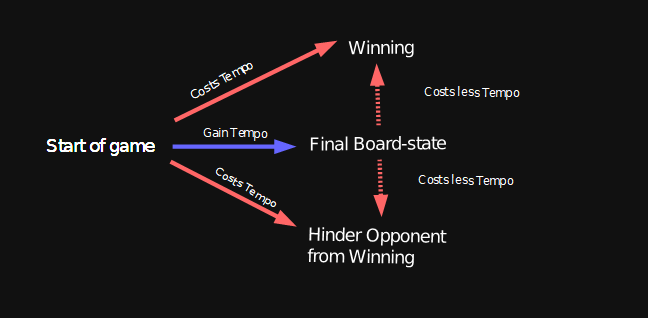

Now, finally, we are going to start talking about spending tempo. In the graph below you can see a simplified view of the decision tree that should be in your head at the start of every turn.

There are two games within the game. The first is the ‘tempo’-game, which is the blue arrow below. The others, the red ones, are progressing towards victory by spending resources.

The entirety of the efficiency article deals with the blue arrow in the graph. However, the absolute most difficult part of playing good Netrunner is mastering those red arrows. It is about ‘leaning in’ to the game.

The first part of this mastery is to recognize when you should choose a red arrow and when you should choose the blue arrow. If you ‘lean out’ you choose to hang back and build your board-state, taking purely efficient moves (blue arrow). You do this when this will gain you more tempo than the opponent will gain from doing the same or you see no efficient way to progress towards your Strategy (winning).

Since you should know how this works by now it will not be covered here, and if you do not i refer you to the article about efficiency.

Disrupt or Progress?

Thus we have two arrows remaining. If you ‘lean in’ you do it to progress your strategy or board-state or to disrupt your opponent’s strategy or board-state. You may do it because an opportunity arises, or you may do it because you are under the pressure of tempo-disadvantage.

First, we will deal with the tempo-game and how that should affect your decision-making. The tempo-game is most relevant at the start of a game, and declines in value closer to the final turns. This is because it is often about long-term tradeoffs.

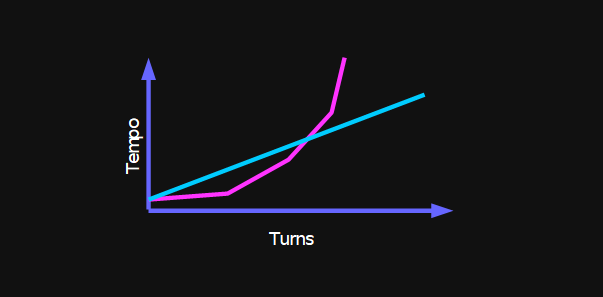

If you are starting a game and you know that your tempo-strategy looks like the blue curve above, while your opponent’s look like the pink curve, what do you do? The first step is recognizing that your opponent will win if left alone, since they will grow an insurmountable tempo-advantage. This is a strategic decision.

Example 1: As a Criminal Runner, since you cannot compete you will need to find a way to disrupt their economy or win the game before they gain the advantage. If you let the Corp get away with fully resolving efficient assets, like campaigns (Nico Campaign, Marilyn Campaign, PAD Campaign) you will eventually give up the tempo-advantage in credits. You should strongly consider leaning in to disable these instead of taking the blue arrow and leaning out.

Example 2: As a glacier Corp, if you’re staring down a Shaper player with Rezeki, Data Folding and DZMZ Optimizers your option is often to try to execute your strategy and win before they are fully set up. If you score agendas that create a rolling advantage, such as Nisei MK II, you create another form of tempo advantage that will allow you to win quickly.

Side Note: Over-investing in Board-State

A mistake that is very common in Netrunner, even at moderate skill levels, is to over-invest in resources. A cost now means you forgo taking actions now, for getting more resources later. The only point of resources is to win, or prevent your opponent from winning. If you will never get to spend these resources, or it allows the opponent to get away with something (like scoring Nisei MK II), this can lose you the game.

Forcing Moves

Apart from tempo-disadvantage, the second type of pressure that you will recognize is called a forcing move. This is when you or your opponent takes an action (or makes a bluff) that can have a significant short-term benefit if left unchecked by the opponent. See ‘Example 2’ above.

These are moves that often require an immediate response from the opponent to prevent a significant shift in tempo, or it could be threatening the game-winning point-7 score. It is specifically not scoring points 1-6 since scoring points do not offer a tempo-advantage or win you the game. However agendas often give other benefits, so allowing the opponent to score still may cause problems.

All-in in poker can be a forcing move.

If your opponent presents a forcing move you need to make a very important tactical decision. Does this move cause the opponent to get the upper hand if successful, and what does it cost you to prevent it? There is one correct answer. You need to have a good sense of the game to be able to see how this move affects the rest of the game.

Practice makes perfect. Make an assumption and follow up on it after the game. Were you correct?

If you are playing for practice, ask your opponent whether they thought you made the right call, and why.

Game Awareness

Information. A critical part of the game. Netrunner is not chess; there is always an element of uncertainty about what your opponent is able to do. Both players’ hands and, of course, the Corp’s board-state, are partly hidden. In addition their deck may be unknown to you, and their strategy with it.

A large part of the game is to ‘see the branches’, to estimate the different paths the game can develop if you make (or don’t make) a certain move. This comes down to card knowledge, of course, but it also comes down to understanding tempo and actively thinking about tempo and strategy in the context of card powers.

Are you ahead or behind in tempo? Has your opponent presented a forcing move? Who wins if the game progresses several turns?

Another part is about estimating the probability of different branches. This is admittedly harder, but necessary to get really good at the game. If you do not calculate your gambles, you are acting blind. Some players do this by playing a lot and building intuition, some do it by doing quick math while playing.

Can you see the branches?

Sequencing

When you start your turn you need to decide what you are going to do with it before taking actions. There is generally an order in which you should do things. This is an easy way for an intermediate player to improve.

Note: This is not always correct, but you should deviate from it with good reason. Also, not all turns will include all of these steps.

First, look at your hand, and the board-state. Decide what you want to do with your cards and actions this turn.

Then, if you intend to draw cards during your turn use your first actions to do so. This is because you get new information that may affect your plan for the turn.

Now it is time to make the large moves. Use any ‘tactical’ econ only if you believe you need it, such as playing a Sure Gamble from hand or clicking Liberated Accounts. If you have decided on a run or two you need to do, do them in the order where the outcome of one would affect the other.

Last in the turn, take any efficiency (tempo-building) moves such as installing econ or equipment you will need in the future. These moves are perfectly known to you, and often require investment before they pay off.

Keep an eye open.

Awareness – Worst Outcome

A critical skill for knowing when you can ‘lean out’ or when you need to ‘lean in’ is to know what your opponent can do next turn. This is something that develops over time while playing Netrunner but is often tied to key cards that are not that numerous to keep track of.

Most often this is a larger part of the Runner’s play, since the Corp can see (and more easily guess at) the Runner’s strategy. It does apply to the Corp however in that the runners hand and deck are unknown.

The first part of this is to estimate the worst outcome and play around that. This is the most common method, especially if you are ahead in tempo you have the luxury to use this method. It is also simpler to calculate.

Example 1: The first time you see how a San San City Grid works in play there was no way for you to prevent it, but the second time? Then you are making an active decision not to check that face-down card knowingly. As soon as your NEH opponent installs a card you need to consider it can be a SanSan. Is it acceptable to you to allow them to use it? It will cost them tempo to use it and score after all. It will cost you tempo to trash it. It may be better to allow the rez and trashing it afterwards, giving them that Beale?

Example 2: Your Personal Evolution opponent installs and double-advances a card in a fortified remote. Playing that ID, they are probably trying to kill you, so what is going on here? They may want you to steal it to follow up with a Punitive Counterstrike, or they may want to save it until a turn they can flatline you with Neurospike. If they are not threatening game-point it may be best to wait and see, potentially letting them score, losing them tempo and building up for another move.

Awareness – Probable Outcome

The second part of this is used when you are under heavy pressure, either by tempo-disadvantage or a forcing move that you cannot ignore. Then you need to rely on probable outcome.

This is also something you should do when the outcome of a branch is less consequential to you. For example which econ asset to install or run, in a non-pressured situation.

Example 3: Your Runner opponent is way ahead in credits, and you do not have a strong late-game strategy. You see a Corroder, but have not seen other breakers. With three agendas in your hand this is not looking good, unless you can score out. You need to make a call whether to use the Enigma on the board, or to draw after a sentry ICE to install ahead of it first. Your choice will depend on the probability of your opponent having drawn the decoder or not.

Example 4: You are running against CtM, and you made a bad call. You’ve been hit with a full Hard–Hitting News and likely smoked with a HPT on your next turn. You’re at 2 credits. You are also on 5 points. You can choose to click 2 credits, and clear two of your four tags. You can also choose to spend your small stack on a final glory run on R&D to see if you can secure the victory. You know you will get in. Your opponent has ~50% deck-access. What is the probability that they’ve drawn two HPT? This will decide your best move.

Side Note: Yomi and Bluffing

Here we are approaching the concept of Yomi, but that will be the content of the final article. I will mention it here, since it contrasts with the type of calculations above that are purely mathematical and probabilistic.

In a pressured situation such as above it is possible to bluff and gain large advantages. Whenever the opponent is forced from worst outcome mentality into probable outcome mentality, they can make a suboptimal move. In addition if they are stuck in worst outcome mentality you can exploit this, since they are very predictable. If you can engineer a situation where they are acting on false information, assumptions or fear you can get away with powerful moves.This is specifically different from tactical decisions since you are not playing the board-state as much as playing the opponent. You are trying to account for what they think.

Conclusion

We have covered tempo in Netrunner and determined that the game is a balance of playing efficiently to accumulate resources and tactically by spending resources on moves that benefit your strategy or disrupt your opponent’s.

We’ve gone into some of the key types of tactical decisions and how they all tie back into tempo, the overall resource of the game. Tempo is the fuel that gets you to your goal, and the game is a tug-of-war to get ahead in it, until the final tactical decisions.

Next time, we will look in detail into your tactical actions and common play-patterns of good play.

Until next time,

/Elusive (& SpencerDub)